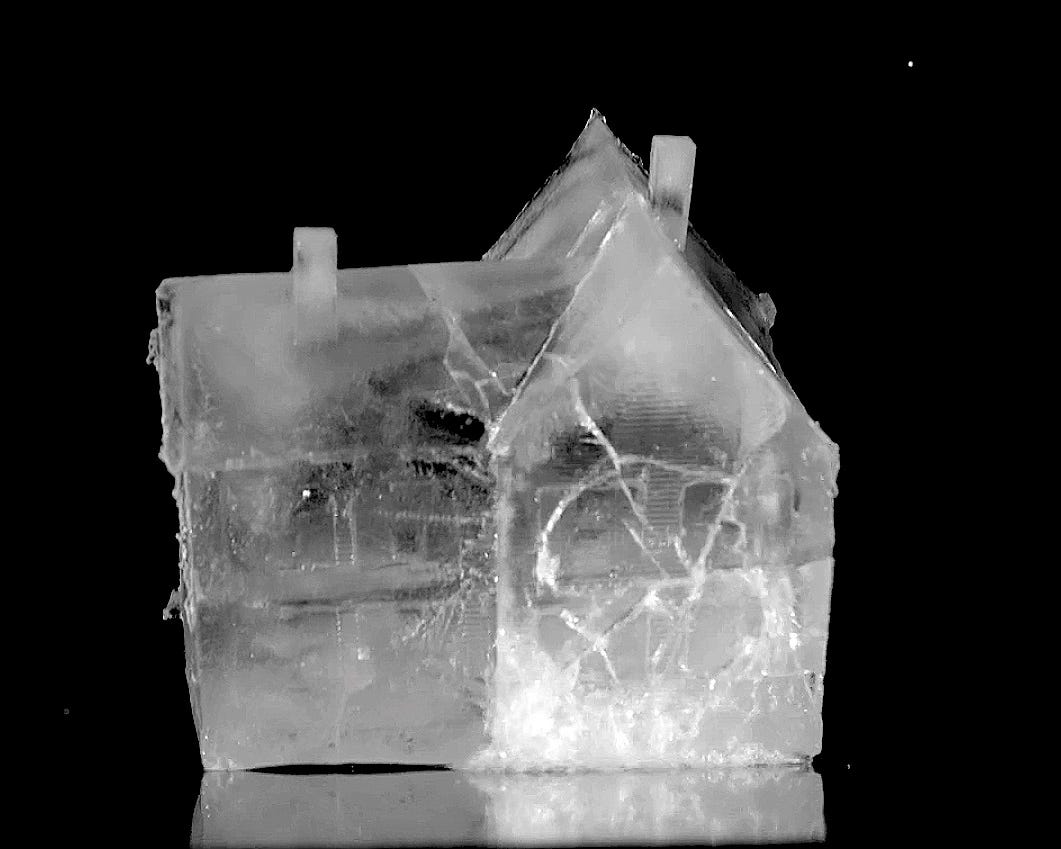

eyes

A poem

ice Ice the ice is coming Oh January, your cold, unforgiving, almost inhumane winds are tearing me apart My eyes are meant to see can’t ignore what the ice is doing to other eyes to other bodies to other humans to other lives “Take shelter,” I heard “Stay your ground” sounds like a threat to my already exhausted soul “The Ice is around the corner, just a piece of ice,” the message my eyes are tired of seeing and ears sad to hear Dear God, made of Goddesses and Gods, Is it true that the storm is coming? The storm that our abuelas talked about, the one that will sweep the Earth of ungrateful visitors? What about the brownies? What about the beans? And dark chocolate? And we can’t forget yellow mangos? Can you, Almighty of thousands of faces, painted in multiple colors, dressed with the same attire of the painter that gave you a face, please give us another chance? And to those who rejoice for the icy Ice coming to tear us apart and see it just as a piece of ice to justify its wants Can you keep them too? They are my brothers and sisters. I know the fear of cold ice arriving. I have seen the pain in Elders’ eyes, remembering when their ice was traded out. At the edge of a time unraveling, I ask for nothing else — only that you protect us all from the storm to come.

Poem by Lorena Saavedra Smith

Photo courtesy of Jessica Segall

What stands out to me is that the poem works on two levels, weather and something human, without forcing them to collapse into one meaning, with subtlety. There's a political message but not a political rant. “Ice” remains unstable: season, force, institution, memory. That instability mirrors the experience you describe, where something dismissed as “just a piece of ice” is a weather phenomenom as well as a social event that devastates real lives.

The opening gives January a moral texture. The cold is “almost inhumane,” and that "almost" matters, suggesting the cruelty may not belong to nature alone, but to people that respond to the designation ICE. From there, the poem commits to witness. The repeated focus on eyes—yours, others’, elders’—is ethical rather than abstract: a refusal to look away, all the bystanders who videotape the brutality.

The quoted commands (“Take shelter,” “Stay your ground”) are especially sharp. They echo emergency language and perhaps reassurance, yet become threats to an exhausted soul. The poem exposes how neutral-sounding words can enact harm and echo the warnings of the whistles and honking of car horns in Minneapolis.

The prayer widens the frame without becoming doctrinal. A divinity of “Goddesses and Gods” allows appeal without hierarchy, while the food list grounds the fear in ordinary, beloved life and reveal the ethnicity of the people at risk. What’s at stake is common decency, not ideology.

Most moving is the refusal to exclude. Asking that those who welcome the ice be kept too, naming them as brothers and sisters, resists moral judgment even while acknowledging damage. The elders’ memory that “their ice was traded out” is a reminder that systems change names, not effects, and we all are endowed with Buddha nature.

The looseness of form matches the unraveling time. The poem doesn’t posture or prescribe. It ends with a restrained, radical plea: protection for all, even when fear pushes us to narrow the circle.